Note

The focus of this post is less about concrete ways to build metrics and more about how we think about prioritization in infrastructure / the downstream impact this has on the metrics we collect and optimize around.

Something I've been thinking about a lot this year is the strange relationship between infrastructure improvements and the metrics we develop around them. There are fundamental KPIs that everyone agrees need to be tracked such as service usage patterns or storage demands over time. But there are also metrics that seem harder to quantify, and so they get neglected (e.g. developer satisfaction scores).

Why is this? In some sense, "infrastructure" means different things to different stakeholders in an organization. To developers, underlying platforms are judged by their ergonomics and availability; they are desired to be relatively seamless and "invisible". To other stakeholders, these same systems might be evaluated by cost, efficiency, or time to market. All of these perspectives are important, but they are certainly not exhaustive.

In practice, I find that the elusive nature of infrastructure, combined with varying perspectives on what should be optimized, often can cause a misdirection in priorities for engineers. And I believe that the availability and prioritization of infrastructure metrics can help us better understand/mitigate this phenomenon.

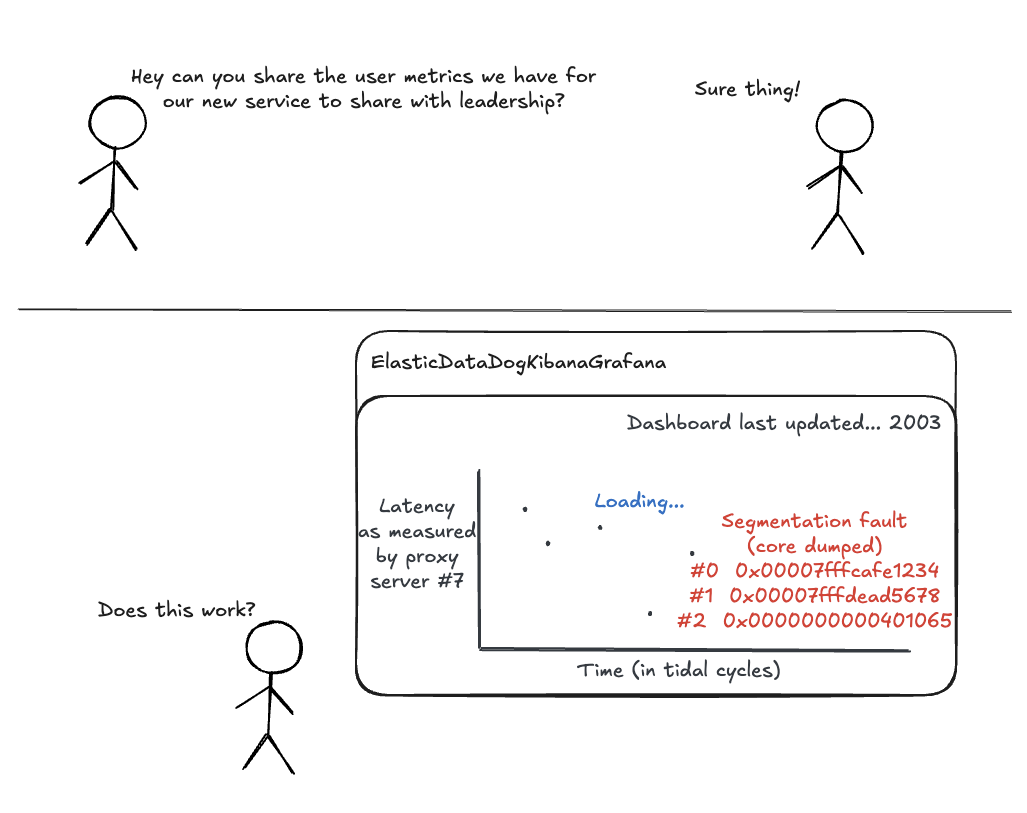

The average search for infrastructure metrics

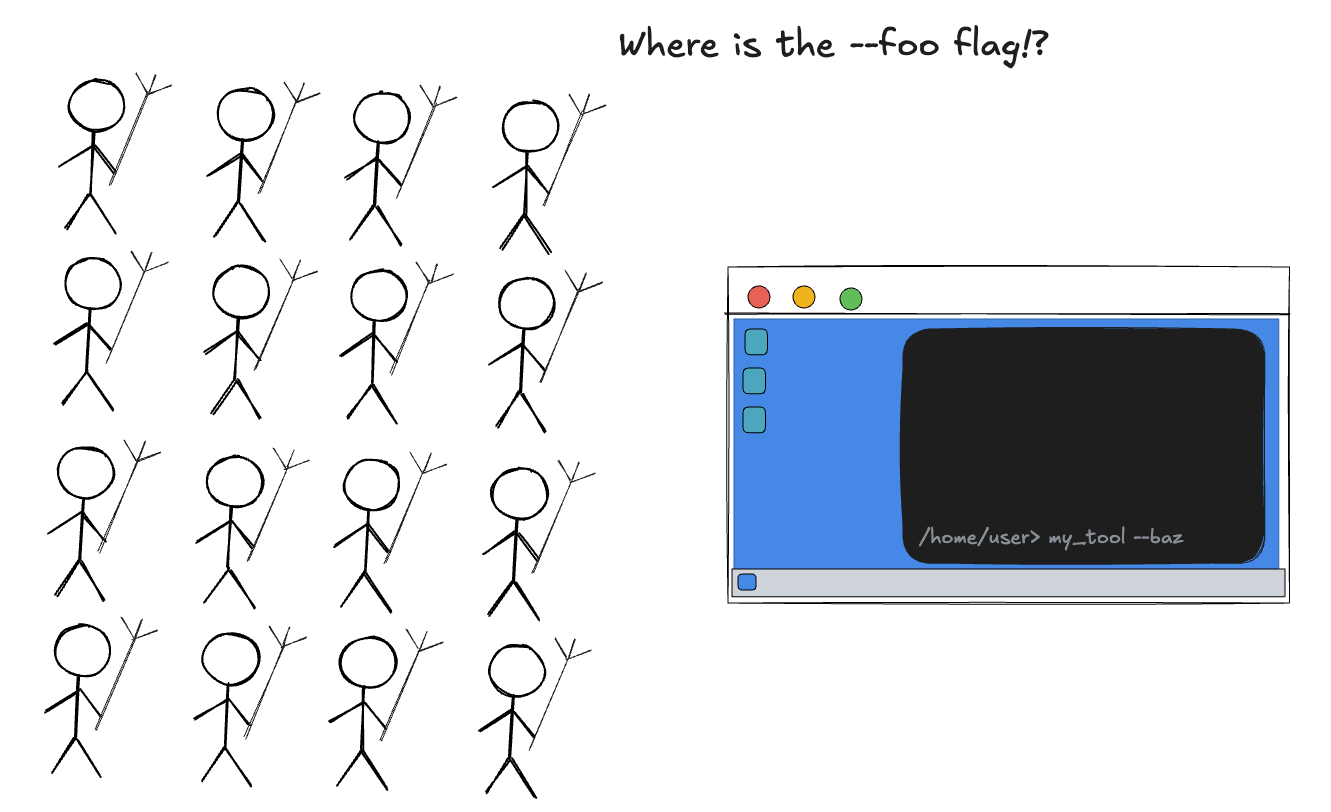

To illustrate this tension, consider a hyperexaggerated scenario: 100 developers message an infrastructure engineer saying, "I really wish we had feature X! If I had feature X, I would be so much more productive!" Excited by such consistent and clear feedback, the engineer begins investigating what it would take to support this feature.

After digging further, it becomes clear that the feature is possible, but architecturally complex enough to require someone working on it full-time for an entire quarter. Undeterred, the engineer makes the case to management. Surely they'll agree that feature X is a high priority! But it turns out that, unknown to the developers, the existing platform's licensing costs just spiked, costing the equivalent of 3 engineers.

Well then. There's clearly a tradeoff here. It is obvious that qualitative developer demands and management-facing business decisions matter in terms of empowering an organization to achieve its goals. But how can the sentiments of the users be preserved in a way that it is still measurable and communicable to other stakeholders? How does the impact of the service's usability actually manifest in practice? And does this lengthy analysis of this feature's decision-making scale to everything that could / should be improved?

In this example, it's not too difficult to reason through the answers. But as you start to unwind more realistic aspects, it becomes clear that:

- • There is a complex relationship between the fine-grained priorities of different stakeholders in an organization

- • Infrastructure metrics become increasingly important for capturing the essence of what different stakeholders prioritize for the business

Why does the developer experience matter? Why not always optimize for backend cost and efficiency?

It seems trivial to ask, but we need to be explicit: the experiences developers have with tools play a critical role in their productivity and effectiveness, regardless of how well those tools achieve "objective" business metrics on paper.

Consider astral.sh's uv as an example. It achieves similar high-level goals as Poetry and Pip, which are all fundamentally package managers. So why was uv suddenly embraced by the Python community

after over a decade of existing tools? Because it lowered the barrier to entry for new Python developers (one central command as a gateway to projects), delivered great developer UX,

and addressed critical pain points in the ecosystem (slow package management, unwieldy platform-specific packages). If we only looked at the written spec of what uv does on paper, it wouldn't seem necessary. But to the average Python developer today, it's a beloved tool.

So yes, there is some separation of concerns between developers and management when it comes to infrastructure priorities. But there's also a strong, often underappreciated relationship between the two. If your tools make engineers substantially happier, they'll be more effective—plain and simple. If management is satisfied by your tools' ability to serve organizational goals, the business will continue to scale and reward the infrastructure with more resources.

Both fronts indirectly support each other. Neglecting one will slowly degrade an organization's productivity over time.

Creating metrics around different types of organizational goals

On one end of the spectrum lie clear, management-facing business metrics (e.g. cost, engineering time, and time to market). On the other end rests a more ambiguous collection of metrics that are more qualitative in nature—the sense that tooling and infrastructure is robust, easy to use, and occasionally even enjoyable. The depth and nuance in this domain is especially pronounced when you're building developer platforms or SDKs. Suddenly the quality of your self-starter documentation, the cleanliness of tooling integrations, and thoughtful programmatic customization become increasingly important to prioritize. Generally, the more "objective" metrics that show direct/immediate business impact are the ones that serve more utility to prioritize. But there is some more thought that should go into the priorities (and surrounding metrics) of other stakeholders. These are some thoughts I have in this regard:

1. Neglected developer needs eventually catch up to organizations

In most cases, minor developer UX issues aren't sufficient to make or break the ability to use a tool or platform—especially if that tool is mandatory for product developers. But over time, leaving these needs unaddressed can snowball into a crisis.

Perhaps the aging system finally collapses under performance issues. Or perhaps it becomes so cumbersome that developers can no longer meet growing business objectives. These are rare occurrences, but not unheard of in the industry.

The more pressing and realistic version of this problem is more subtle: neglected infrastructure gradually slows down an organization, making it harder to tackle difficult problems quickly. This is precisely why we need to understand and measure these issues before they become critical.

2. Developer needs are often obfuscated from management (and vice versa)

In the exaggerated hypothetical scenario provided earlier, management might be able to see 100 developers holding pitchforks demanding a feature. Unsurprisingly, this tends to be slightly different from reality. One example that comes to mind is having bespoke tooling.

In such a scenario, new hires will struggle to develop a deep understanding of the tooling nuances while experienced developers remain blissfully unaware—either due to their tenure or because they've learned workarounds around the UX issues. This is an insidious problem. You'll only ever see a small fraction of engineers deeply impacted by specific tooling issues, while everyone else is either unaware or has chosen to turn a blind eye to the inefficiencies.

By definition, such issues rarely surface to management unless a new hire is particularly vocal and influential. These problems might manifest most clearly through long onboarding times, but even then they may not appear in developer happiness surveys. I don't mean to suggest this is necessarily a crisis. Rather, I want to emphasize that structural differences in priorities can subversively allow developer issues to go unnoticed and unaddressed.

On the flip side, there are sometimes infrastructure needs that promote management objectives without an obvious selling point to users. My colleague Jagdish would describe these as "medicine". Maybe the user wants infinite allocations of compute and storage for their personal regressions. Maybe they want to ensure that their batch jobs are always scheduled immediately at the front of the queue. In any case, infrastructure engineers obviously can't satisfy the extremities of such requests, and instead are focused on delivering high value to the organization as a whole. The user may not perceive that this is the optimal decision, but it will end up benefitting them and speeding up the organization.

3. Finding ways to connect different types of stakeholders can be extremely powerful

Oftentimes, the most rapid progress I see towards organizational goals happens when a project or plan connects stakeholders together. A little bit of thoughtfulness goes a long way in snowballing the impact of an investment. Instead of thinking "if I just had N more engineers / management signoff to make it happen," I've found it more productive to think, "how can we unite people around a common goal"? When people are passionate about an idea and see that it connects to their goals, they naturally bring it into fruition. Of course, not every project embodies an idea that seems intrinsically perfect for every stakeholder. But by thinking about these different priorities and how to build metrics around them, the friction to make something happen will decrease significantly.

4. Some infrastructure metrics are (substantially) easier to quantify than others

It's surprising how often I've seen even straightforward, critical metrics such as service health or response throughput be under-quantified in organizations.

Given this reality, it's hardly surprising that more qualitative metrics like developer happiness, onboarding friction, and support responsiveness are measured even less frequently. This makes sense when you consider the "hidden" nature of infrastructure work: if it's working well, it's invisible. If it's not, the symptoms are diffuse and hard to pin down.

For the most part, the quantitative metrics are far easier to collect because they can simply be automated. Even if it requires more thoughtfulness to curate a special mechanism that can track information in a distributed environment, it is still a direct, tractable engineering problem.

Qualitative metrics I find to be extremely rare, partially because they are difficult to collect, and partially because they can sometimes be hard to define. Some may not even agree on the importance of qualitative metrics. And certainly, the goal is not to invest time in an area that doesn't provide direct benefit. Instead it's just to give thought to finding ways to concretely track progress towards meaningful goals.

So what goes under-measured?

These are a few areas where I've found myself wanting a way to show measurable comparisons to help add weight behind engineering proposals or initiatives.

-

1.

Maintenance cost

Now more than ever it's easy to ship something quickly that will not scale or not be maintainable in the long term. This is related to complexity but I think it also encompasses things like "TCO" (total cost of ownership) in terms of engineers adding features, fixing bugs, and responding to incidents.

-

2.

User satisfaction

Developer surveys and A/B testing to understand user preferences can go a long way in helping folks speed up their daily development; And, it helps to spread the awareness of issues to management.

-

3.

System complexity

Software complexity is something that has been studied for a long time! I think today, the more we can reason about this on a more distributed level, the more we can sustain our services for the long term.

-

5.

"Proprietariness"

The semiconductor industry certainly has no shortage of internal development practices. Quantifying the amount of internal SW in a given system helps to understand the internal maintenance cost (especially if the benefits of similar OSS are missed!).

I hope to share this as a way of promoting mindfulness towards infrastructure metrics and thinking more critically about prioritization for different stakeholders. We may not always have time to implement these ideas, but thinking about them can help us be more cognizant of our blindspots and inform our decision-making.